Table of Contents

A term sheet is a non-binding agreement that summarizes the fundamental terms and conditions under which an investment will be made. For every entrepreneur, having this document on the table is an important milestone, an affirmation of their vision and hard work. However, this excitement can quickly turn into a minefield. Although the phrase “non-binding” sounds reassuring, the points agreed here almost always carry over into the final and binding investment agreements. Changing them later is both difficult and damaging to trust. Therefore, understanding this document, which is the plan for the future relationship with the investor, is critical to a startup’s long-term success. Particular attention should be paid because certain provisions such as confidentiality, exclusivity and expense sharing can be binding even at the term sheet stage. The definitions of items such as the pre-money/post-money distinction, the option pool and pro-rata rights should also be clarified early.

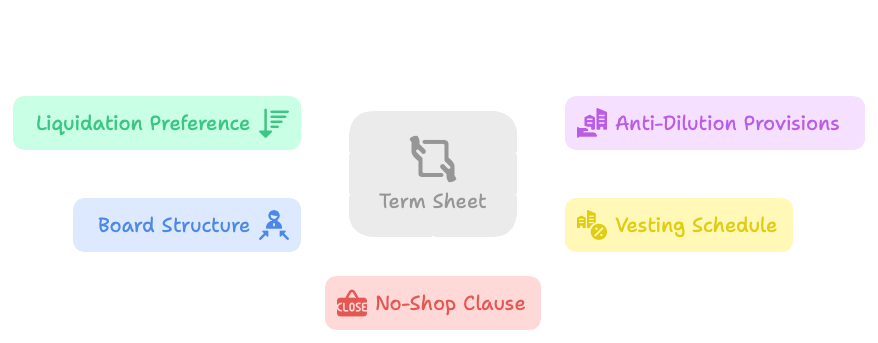

- Critical Points to Watch in a Term Sheet

Investors prepare term sheets to protect their capital and maximize their returns. Although most provisions are standard, some can be overly aggressive and put the entrepreneur at a disadvantage. Here are the main areas that should be analyzed. Because of the interaction among provisions, it should not be forgotten that terms that seem reasonable individually can create imbalance in the aggregate.

- Liquidation Preference

This clause determines the order of payment in a “liquidation event” such as a merger, acquisition or the winding down of the company. The standard arrangement is a “1x non-participating” preference; this means investors first recover their investment before other shareholders receive any proceeds. What must be watched is the participating liquidation preference (often called “double-dipping”). With this provision, investors first take their money back and then also receive their pro-rata share of the remaining proceeds. Another point of caution is “multiple” participating preference (e.g., 2x or 3x), which can leave founders with almost nothing in a modest exit. The priority ordering among rounds (senior or pari passu) should be stated clearly, and if there is participating preference, a reasonable cap should be requested.

- Anti-Dilution Provisions: Protection Against Down-Round Valuation Decreases

These provisions protect investors if the company later raises capital at a lower valuation (a “down round”). The fairest and most common approach is the “broad-based weighted average” formula, which adjusts the investor’s price based on the size and price of the new round. The red flag here is a full-ratchet anti-dilution provision. This highly aggressive term reprices the investor’s shares directly to the new, lower price regardless of how many new shares are issued. It can severely dilute founders and early employees and should be opposed. It should be confirmed that “broad-based” truly relies on the fully diluted share count, and reasonable carve-outs such as ESOP increases and SAFE conversions should be specified.

- Vesting Schedule

Vesting aligns founders’ and employees’ incentives with the long-term success of the company by having equity earned over time. The market standard is a four-year vesting schedule with a one-year “cliff.” This means nothing vests in the first year, but on the first anniversary 25% becomes yours, with the remainder vesting monthly over the following three years. Care should be taken with unusually long vesting periods (five or six years), with failing to credit time already spent at the company, or with an investor demanding accelerated vesting for themself in the event a founder is terminated. Definitions of good/bad leaver scenarios and the repurchase price should be clarified for departures, and double-trigger acceleration should be structured on reasonable terms.

- Board Structure

The board makes all major company decisions; therefore, losing control of the board means losing control of the company. For an early-stage startup, a three-member board is common and balanced: one founder, one investor, and one independent member mutually agreed by both sides. What should be avoided is an investor immediately demanding majority control of the board seats. This gives them the power to make critical decisions, including replacing the CEO, without your approval. Board observer rights, quorum thresholds and the list of protective provisions should be kept limited and measured so as not to undermine operational agility.

- No-Shop Clause:The Risks of One-Sided Commitment

This clause prevents soliciting investment offers from other potential investors for a certain period while the current investor conducts due diligence. A reasonable no-shop period is 30–45 days. This is sufficient time for the investor to complete their work without the concern of a competing offer. A long period such as 90 days or more should be avoided. This can be a strategy to buy time and, if the deal falls through, can leave you with very little leverage or time to secure other funding. The period should be aligned with the diligence timetable, include staged checkpoints, and, if necessary, be supported with fiduciary out exceptions.

Effective Negotiation Strategies for Entrepreneurs

Negotiating a term sheet does not mean being combative. It is about advocating for a fair deal that establishes a healthy, long-term partnership. The process should be conducted in a disciplined manner with a data room, a shared set of metrics and a clear timetable.

- Knowing Value and Market Standards

Even before seeing a term sheet, it should be researched what kinds of deals companies at a similar stage are making. It is advisable to speak with other founders, advisors and attorneys. Knowing what is “standard” in the market is the best defense against aggressive terms and the basis for a confident negotiation. Sources such as NVCA templates and local market reports should be compared, and benchmarks should be made on a like-for-like basis.

- Prioritizing Demands

Before starting, it should be decided what is most important for the leadership. Valuation? Maintaining control of the board? Protecting the equity stake from excessive dilution? Instead of getting hung up on every minor clause, energy should be focused on the two or three top priorities. A pre-defined “must-have/nice-to-have/waivable” framework and consistent trade-off options should establish a coherent bargaining position.

- Creating Leverage with Competitive Offers

The best way to secure a good deal is to have alternatives. If possible, multiple investors should be engaged at the same time. Having a competing term sheet, even if not intended to be accepted, provides tremendous leverage to negotiate better terms with the preferred investor. Negotiations should be synchronized using a single timetable and a matched information set while respecting no-shop and confidentiality boundaries.

- Obtaining Legal Counsel

A term sheet should never be signed without review by an experienced startup attorney. They have seen hundreds of these documents and can identify problematic provisions that might be overlooked. Legal fees are a small price to pay to set the right foundation for the partnership with investors. A well-negotiated agreement not only finances a company but also preserves your vision and lays the groundwork for a healthy, long-term relationship built on shared success. Fixed-fee scope clarity, advice on tax and ESOP implications, and a written decision log should secure the pr